BLOG

|

|

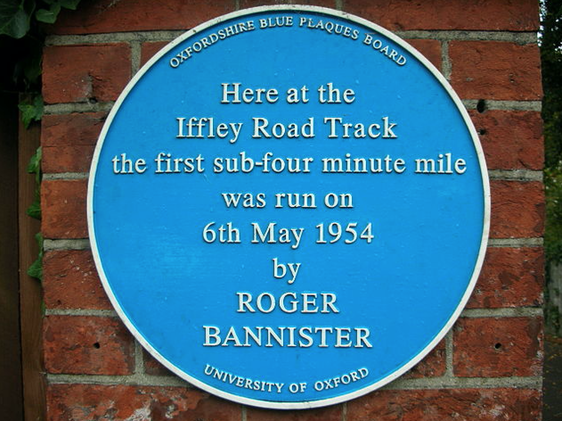

MARCH 3, 2018, ROGER BANNISTER PASSED AWAY at the age of 88 years. If you aren’t already aware, the United Kingdom’s Sir Bannister was the first athlete to run the mile distance race in under 4 minutes on May 6, 1954. He was a medical student at St. Mary’s Hospital in London. With little time to devote to serious training, he reportedly ran on a track near the hospital during his lunch hour.

An article in the scientific journal, Cell Metabolism recounted that he used “the 9-minute jog to a local track to warm up, after which he promptly ran 10 x 400m in a little over 60 sec each, with 2 min recovery. He then ran back to work leaving 15 min to eat his lunch and (hopefully) shower.” Although he made sport’s history at Iffley Road Track in Oxford that night in 1954, Bannister was proudest of his achievements in academic medicine; he was an eminent neurologist and neuroscience researcher. His record lasted only 46 days. Of course there was more to Bannister’s training methods than noon-hour track sessions, but it was his high intensity interval work that was singled out for mention in the Cell Metabolism article, “Sprinting Toward Fitness”, written by Drs. Martin J. Gibala and John A. Hawley. The authors begin their discussion by explaining that although intense interval training has recently received attention for its potential to improve the health of persons with diseases originating from lack of exercise, it has been recognized “for over a century” by coaches and athletes as performance enhancing. By employing sprint training, Bannister and his coaches had been following the lead of past, pioneering Finnish and innovative German trainers of the 1920’s and 30’s. The article indicates that scientific investigation into the physiological basis of the intense interval training method was not initiated until the 1960’s. Over the decades, it reports, researchers came to recognize that intense interval exercise could be of benefit not only to elite athletes but to any person wishing to “condition himself for health purposes”. And ultimately to those who could not tolerate continuous exercise at a moderate level, like patients with heart failure. Gibala and Hawley make the argument that in present day, “identification of time-efficient exercise strategies that confer health benefits”, like intense interval training, “could favorably impact public health by reducing the economic burden associated with inactivity related disorders.” “Lack of time” they propose, would no longer be a barrier to getting regular physical activity. With this historical perspective, the article begins the discussion of interval training, which they say can be “broadly classified into two categories: high intensity interval training (HIIT) and sprint interval training” (SIT). Roughly, HIIT involves less-than-all-out power/speed efforts at or above 80% maximal, and SIT involves an “all-out” efforts, at or above 100% maximal, as determined by each individual's VO2max measurement. For comparison, moderate intensity CONTINUOUS training (MICT) is performed at about 50% effort. Tabata and colleagues are identified as making important contributions to the study of SIT exercise, which is described as a particularly POTENT variation of intensity training. The gist of Tabata’s and others’ research has shown that that the body’s beneficial, clinically significant, physiological adaptations to MICT exercise performed over longer sessions (45+ minutes) could be obtained with intervals of greater, more intense effort, but measured in seconds, and separated by recovery periods of a few minutes. In one such study, 60 seconds of SIT within in a total 10-minute period of exercise resulted in the same changes brought about by 50 minutes of MICT. The authors say that this evidence is begging scientists to determine how “a few hard sprints in such a short intervention period elicit such profound remodeling of physiological systems” They explain the different molecular-level physiological adaptations associated with 3 different modes of exercise:

The scientists put forth the concept that an “acute” exercise session of any training type sends a “signal” to the body that induces widespread, unseen physiological adaptations to maintain normal functioning during this period of increased metabolic muscle activity and whole-body oxygen demand. However, in order for exercise to “induce physiological adaptations that ultimately result in long term phenotypic changes”, or observable alterations in tissues and organs, a certain “threshold stimulus” must be exceeded in each session. [Non-research example: a ‘threshold stimulus’ signal for me to diet and exercise seriously might be reached on the first day of a run/walk training plan for a late spring race, when my weight on the scale is 10 pounds heavier and best mile pace is 1.5-2 minutes slower than in the previous fall. A 30 second/mile slower pace plus 2-pound gain would not reach the ‘threshold’ level that prompted my taking daily sufficient actions that, over the long term, would bring bodyweight and pace-time down] The second- to- last portion of the article discusses how the body-wide changes evoked by MICT exercise sessions compare with those caused by HIIT and SIT. In summary, “in contrast to MICT, the rate of change of cellular dynamics and disturbances to whole body homeostasis induced by intermittent exercise and SIT in particular, is extensive”. In my understanding, this means that although an intense training effort is very brief in duration, the signals sent to the rest of the body systems seem to totally shake up the body’s status quo. HIIIT and SIT “evoke perturbations to both local (muscle) and systemic (cardio-, vascular, respiratory, neural, and hormonal) homeostasis.” The publication suggests that intensity level may not be the only aspect of HIIT and SIT that cause such exercise to lead to “superior” or at least similar beneficial body-wide adaptations as MICT, despite less total work being performed. The “’stop-start’ nature of INTERMITTENT exercise and the ‘spikes’ in various intra-cellular signaling pathways” may represent one mechanism that explains such differences in skeletal muscle response. There’s a bit more ‘intense’ science discussion related to the intermittent/interval aspect of this training and how it may also be key to induction of changes that lead to improved health. Finally, Gibala and Hawley suggest the directions future research could take to explain how and why SIT is able to fight chronic metabolic diseases. The information could be helpful in the development of personalized exercise prescriptions, they propose, which will allow individuals to obtain the maximum benefits of regular exercise activity; one option among many possible interventions. “After all,” they conclude, “interval training is just one aspect of the multi-faceted, periodized training strategies that have been used by competitive athletes for over the century.” And that’s the message we can take from all this science. THAT HIGH INTENSITY INTERVAL TRAINING ESPECIALLY SIT, CAN ACCOMPLISH IN A SHORT PERIOD OF TIME, WITH LESS WEAR AND TEAR ON OUR BODIES, THAN WHAT WE HOPE TO GET FROM REGULAR CONTINUOUS AEROBIC EXERCISE. Perhaps more, as was shown by Sir Roger Bannister in the 1950’s. We may not have information about our individual maximal capacity to exactly follow SIT protocols published by scientists. But we can certainly change some MICT-type workouts to HIIT sessions that alternate short periods of moderate-to-very vigorous effort with longer recovery intervals of lower effort, in a start-stop manner. If we become comfortable with such training methods now, later on, when time available for exercise decreases, physical performance is limited, or our health declines we can more easily maintain the benefits we receive from regular exercise. Mentally and emotionally we might not feel cheated or lessened by circumstance or disability. “Sprinting forward; where to from here?” the scientists asked. To the road, the gym, to the exercise floor we can answer. RUN & MOVE HAPPY! NOTE: When I contacted the corresponding author about his work, Dr. John A. Hawley, Director of the Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research and of the Exercise and Nutrition Research Program of the Australian Catholic University, Melbourne commented: “The bottom line is that HIT provokes widespread changes in muscle signaling pathways and metabolism that are also seen with much longer workouts. People also enjoy HIT a lot more than cycling/running for an hour or so.” https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2018/mar/04/sir-roger-bannister-obituary http://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/pdf/S1550-4131(17)30237-1.pdf By Photograph by user: Jonathan Bowen - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1725293

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BRIDGE TO PHYSICAL SELF

Running, walking, and fitness activities enable us to experience our physical selves in a world mostly accessed through use of fingers on a mobile device. AuthorEARNED RUNS is edited and authored by me, runner and founder. In 1978 I began participating in 10K road races before 5Ks were common. I've been a dietitian, practiced and taught clinical pathology, and been involved with research that utilized pathology. I am fascinated with understanding the origins of disease as well as health and longevity. Archives

November 2023

CategoriesNew! Search Box

Earned Runs is now searchable! Check it out...

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed